MALAYSIA

Malaysia’s electoral system follows the Westminster parliamentary model, with the government elected through a first-past-the-post or simple majority system. From Malaya’s independence in 1957 through the formation of Malaysia in 1963 until the 2018 general election, the minimum voting age was 21.

This excluded many Malaysian adults, with students in higher education institutions making up no less than a third of this number. This has changed since the election of 2018 and student issues have risen up the agenda.

Student voices matter

The current prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, was among the more vocal student activists when rural poverty was a major issue of concern among university students in the 1960s, causing much discomfort to the federal government then.

However, since the passing of the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971 (UUCA), later amended in 1975 and 1995, student activism, shackled by the enactment of this Act, waned for more than 40 years. The Act made student movement activism difficult.

Depending on the overall political climate and students’ leadership qualities, politicians and political parties were, or were not, able to champion their issues and grievances beyond the gates of universities.

Student voices gaining momentum

The 13th Malaysian general election held on 5 May 2013 witnessed the revival of student activism in Malaysia.

The student movement had gained from a slight loosening of the UUCA in 2012 when the then minister of higher education Khaled Nordin pushed for its amendment, thus paving the way for limited student participation in the 2013 general election. However, only students aged 21 and above were eligible to vote.

The major concern of students was free education and the terms of repayment of student loans. Another item on their agenda, that had the moral support of academic staff, was

university leadership, or rather the lack of it, which they argued was the direct effect of the UUCA and other civil service-related General Orders for academic staff.

Their focus was to regain the university autonomy that had been lost in the 1970s, with the government retaining ultimate control and monitoring the implementation of higher education.

Courses and programmes offered at universities are monitored and controlled by the higher education department of the Ministry of Education (later Higher Education). Furthermore, the Malaysian Qualifications Agency, established in 2007, has arguably usurped the role of the university senate in academic matters.

With student activism and the opposition political parties’ battle cry for change, the 2018 general election provided students and academic staff with a way to demand substantive changes in the delivery of higher education.

GE14 and higher education

At the Malaysian general election 2018 (GE14), held on 9 May 2018, a higher education issue of interest raised by the opposition party was the National Higher Education Fund Corporation (PTPTN), an authority responsible for disbursing study loans to Malaysian students pursuing tertiary education.

The study loan conditions stipulated that, upon completion of their studies, students were required to arrange for repayment of their loans within six months. However, with a slow economy and widespread unemployment, many graduates struggled to secure jobs with decent salaries and many felt that PTPTN had become a burden.

Since the GE14, student loan repayment has become a major issue for students with regard to their engagement with political parties. Consequently, in the run-up to GE14, the opposition centre-left coalition Pakatan Harapan, seeking to attract the attention of younger voters, pledged to extend the repayment period for borrowers until their monthly income reached RM4,000 (approximately US$880).

Once in power, however, the Pakatan Harapan found this pledge difficult to implement because, on average, it would take many years to secure that income level as entry level salary is low for graduates. Furthermore, with delayed repayment, the sustainability of the fund itself was highly questionable.

GE15 and higher education

The recent Malaysian general election, which took place in November 2022, was of great interest, particularly because the vote was extended to over 18s, which included those entering and those already in tertiary and higher education institutions.

For GE15, 1.2 million new voters aged 18 to 20 years, 38% of whom were students in higher education, were eligible to vote for the first time. This group wanted to be heard, believing that their opinions should matter to politicians. As these new student voters could swing the general election result, issues concerning higher education and student welfare were carefully crafted in the different party manifestos.

While all competing political parties campaigned on issues relating to student loans and the repayment period, the Barisan Nasional – the National Front party – also offered free higher education for B40 families (the bottom 40% household income group, roughly about 2.7 million households with a mean monthly household income of RM3,166 or about US$730 per month) as opposed to free education for all.

Households in the M40 (medium income) category would be eligible for full student loans. Interestingly, gap years, flexible learning and digitalisation of learning for students, female leadership and equity issues were also included in the party’s offerings.

The Pakatan Harapan coalition focused more on improving university governance and the establishment of more regional universities in the two Malaysian regions in Borneo.

None of the parties mentioned how they would plan to secure value for money in relation to the additional investment in higher education, or support higher education institutions to make efficiency savings where needed.

After the 2022 election – what really matters

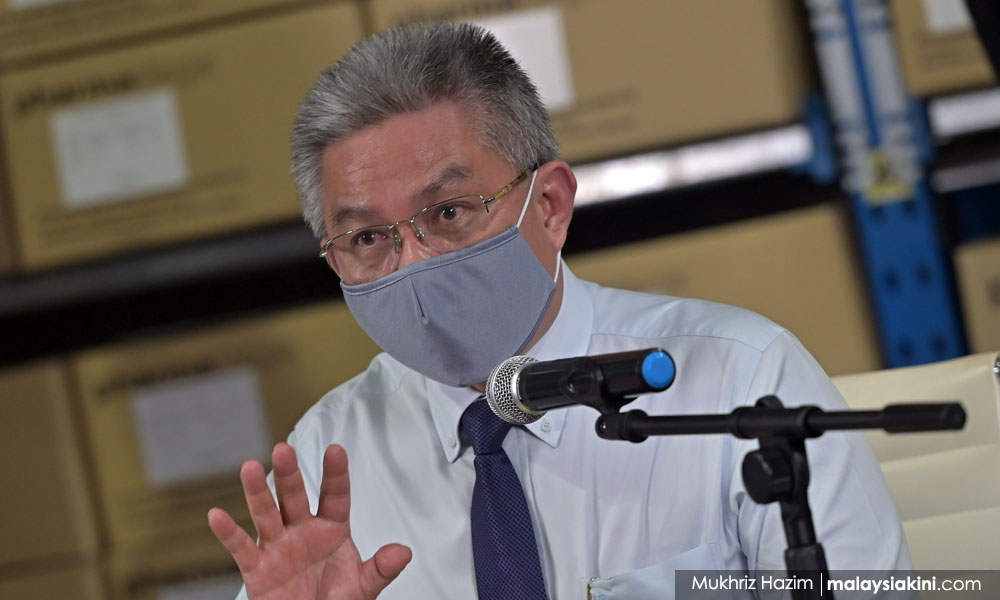

After the GE15, the unity government, comprising various political groupings and led by Pakatan Harapan and Barisan Nasional, appointed Mohamed Khaled Nordin as minister for higher education for the second time.

Mohamed Khaled Nordin should be able to hit the ground running and implement what has been offered and promised in the manifestos of members of the unity government.

While many issues pertaining to higher education were raised in the most recent election, practicality issues may mean that only the critical ones get implemented.

Based on his institutional memory and understanding of the higher education system, Khaled Nordin should be able to implement policies that really matter, based on the best research available, to place Malaysian higher education on a different trajectory in a post-pandemic scenario.

Morshidi Sirat is emeritus professor at Universiti Sains Malaysia; Norzaini Azman is professor of higher education at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia; and Mohd Izani Mohd Zain is an associate professor of politics and government studies at Universiti Putra Malaysia. The authors are members of the Malaysian Society for Research and Higher Education Policy Development (PenDaPaT).